One of the most important concerns of a teacher is to make sure that all of his students are actually working. In this regard, the language lessons are particularly at risk, because oral activities take a greater part in them.

When you do an exercise in written, all the students try to answer the questions simultaneously, obviously some of them with more seriousness than the others, but, still, all of them have to do at least something to avoid troubles when it comes to the correction. And it’s not difficult for the teacher to walk between the ranks and to look after the children. During an oral lesson, the attention of the teacher is usually taken by the lesson itself. It’s less easy to awake the lazy students.

It’s a common practice for language teachers to simply ask questions and wait for the students to answer them spontaneously. It’s not difficult to see the limitations of such a practice. When the teacher relies on volunteers, he tends to engage the conversation with only a handful of students. In the best cases about 10 or 15 students will actually work. More likely, the teacher will discuss with the 4 or 5 best students, with 10 more trying their best to get a little share of the speaking time. It’s very unlikely that a shy or a slow student will ever be able to open his mouth in a constructive way. If he feels not confortable enough to raise his hand at once, there will ever be a faster student to answer the question, while he’s still preparing his own answer. It can mean 6 years of suffering for a conscientious teenager. When it comes to evaluation, the poor guy who has not been able to participate is punished not for his lack of work or his poor knowledge, but for his shyness. A quick calculation will expose the difficult of overcoming one’s shyness. If there are 30 students in a class, each one has a window of less than 2 minutes per lesson to try and tell something. No wonder that some children get bored or just give up.

However, there are ways to increase the attention of the students. Here I will make some suggestions. I don’t pretend to have the ultimate method of teaching. It’s up to the teacher to choose his own method according to his own personality and to the mood of the class.

Firstly, when he wants to question the class, the teacher should ask students specifically, not always the volunteers, but also the other ones. And he should ask the question first and then designate the speaker randomly. Thus, he obliges all of the students to mentally prepare some answer, or at least to listen to the question. No one knows who will have to work, so everybody gets ready. If, on the contrary, the teacher questions the students always in the same order or only the students who want to be questioned, a lot of them will just wait for their classmates to do all the hard work in their stead. This solution increases the students’ attention significantly. Another advantage of choosing the speaker is that the teacher will be less reluctant to work on the accuracy of the speech. In fact, when you rely on the students’ good will, you may fear to discourage them by too much attention on mistakes. It’s a really unpleasant experience for a teacher to have a silent unwilling class in front of him. But why remain stuck? Just decide who will work! Arbitrarily if needed. The pupils may be a little bit reluctant at first, but in the end, everybody will feel better. I don’t mean that the teacher should refuse spontaneous participation, only that it should not be a limitation. The teacher has to choose according to the situation. To keep momentum in his lesson, he has to find some balance between the fast and the slow students or between accuracy and fluency. This simple solution however doesn’t increase the average speaking time. Even if the repartition of this time is better, the students still have less than 2 minutes each.

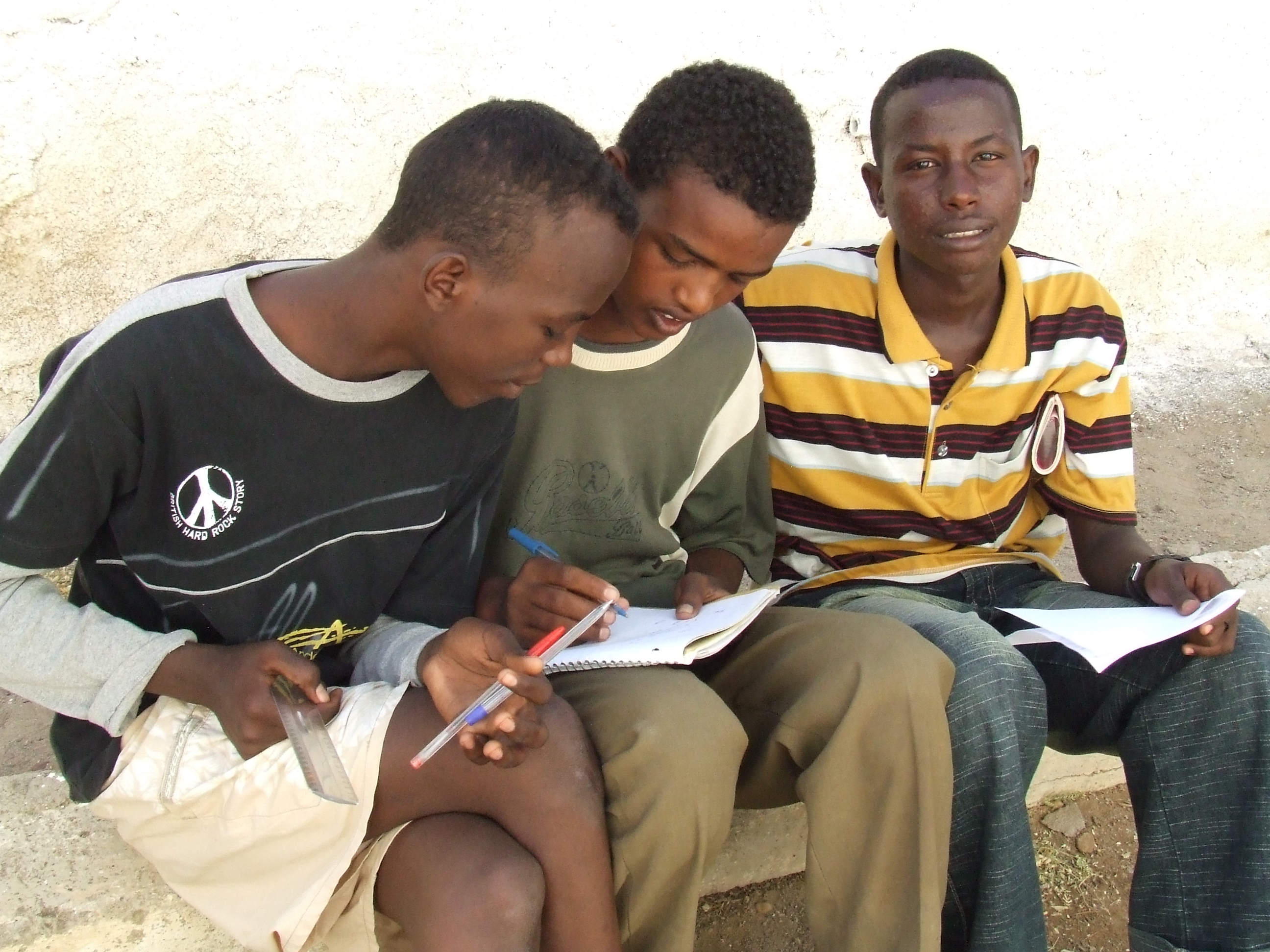

The other solution, obviously, is to have them speak together in small groups. This is not an easy solution, because it can bring disorder in the classroom and it’s more difficult to assess the accuracy of many speeches that take place at the same time. Being aware of the risk allows you to address it effectively. By the way, it’s not very different from the exercises that we do in written. Usually you correct them collectively and you don’t bother to verify the accuracy of the production of each and every student. The teacher can ask the student to discuss in pairs. Small groups are better, because it’s easier to get your turn in the conversation and your are less tempted to rely on the others’ work. In my opinion, a workgroup should not comprehend more than 4 persons, maybe 5 if they have very specific roles (for instance during a trial simulation). Then, the teacher can make a collective correction by choosing one group to present the conversation in front of all. Knowing that you will be looked at by all your classmates is a strong incentive to behave and try your best.

This work in groups can thus be seen for what it has to be, a mere training for something more important. I would say that the whole affair is a training for real life, but that’s another question.

Remark to get a broader view on the issue

In all the activities that involve a high level of creativity or a high level of initiative, the distribution of success tends to be very unequal and to follow a Pareto distribution. It means that a little percentage of the people tend to do most of the productive job, earn most of the income, and so on. A very little proportion of the artists provide the bulk of the concerts places, and sell the majority of the disks.

At war, a tiny number of soldiers, with a killer’s mind, are responsible of the vast majority of the enemy casualties. Most people don’t even try to kill and shoot a bullet from time to time in order to follow the orders and defend themselves a little bit. It’s well-documented in all the social sciences.

The combination of competition and creativity always involves some kind of selection. Those who are already good can improve themselves. Those who aren’t are discourage or can just remain still because only the best really matters. This reinforcement process is sometimes called the Matthew effect.

One of the consequences in pedagogy is that competition can present some risks as well as the activities that require a lot of creativity and autonomy. Those activities however are essential, because the students need to learn how to solve problems by themselves, they must become autonomous adults. They shoud learn to take initiatives. Those risks must be taken into account, not avoided. The task of the teacher will be to create a reasonnably safe environnement in which the students can try, take initiatives, even fail sometimes without being judged too harshly, for instance, without being laughed at by their classmates, or without being under the impression that only the best ones matter. In this regard, school should be like a game. You win sometimes, and it’s great. You loose sometimes, and it’s OK. The fake dead can rise up after the play. After all, from an etymological point of view, “school” means “game” (in Greek skhole).

Poster un Commentaire

Vous devez vous connecter pour publier un commentaire.