This is the full text of my speech during the Cambodia International Conference on Mentoring Educators.

Real issues, bad questions

Take a young teacher or a journalist, and he’s asking you: “What is the best teaching method?” Everybody has some opinion on this. Your minister, your parents, even your kids. Annoying, isn’t it? As educators, you want to base your response on solid research. You might already have a plan to promote constructivism, or some procedures inspired by behaviorism. Maybe you are trying to salvage traditional practices by calling upon neurosciences. I’m a teacher trainer myself. I’ve written large parts of the syllabus of the New Generation Pedagogical Research Center in Phnom-Penh. But if you ask me that question, I’ll answer you: “I don’t know.” I don’t know because nobody really knows.

That question is a very serious one, but very poorly formulated. It lacks the most important element: context. That’s what I’d call low-resolution thinking. We don’t analyze the problem with the level of details that would be necessary. It’s important both theoretically and practically. It has catastrophic consequences in pedagogical research, teacher training and educational policies.

Teaching is similar to engineering. “What is the best plane?” For a decent engineer, the question is meaningless. The best plane for what? What are your objectives? Do you want to transport merchandise or do you want to fight? Do you fight low-tech insurgents or do you want to fight Russia? Do you need to go fast or do you need to carry a lot of people? What is your budget? What is the length of the runway?

Like medicine or engineering, teaching is an art, in the old meaning of the term, a technique with its know-how. It’s more or less based on science but it isn’t a science. Teaching is directed toward action. We can learn psychology, epistemology, social study, even neurology to establish some foundations. But let’s be honest, our background sciences are not as solid as biology and physics. What matters is that the children learn. Most of the time, we don’t really know how it happens. We just observe that it works. Or not. I don’t want to frighten you, but it is still often the case in medicine. Somehow, the drug saves you, or kills you. Researchers have some basic understanding of the action mechanism, but they don’t control all the side-effects. And it is very likely that your doctor just follows the instructions of the researchers.

There is no such thing as a best teaching method. Which subject are you teaching? To whom? Are your students slow-learners? Do they have disabilities? Do they master the prerequisites? Are they comfortable with social interactions? What do they want to become? Lawyers? Stockbrokers? Politicians? Or maybe they just want to be happy? Depending on your objectives, or on the student’s objectives, a method can be more relevant than the other. Rote memory is necessary sometimes.

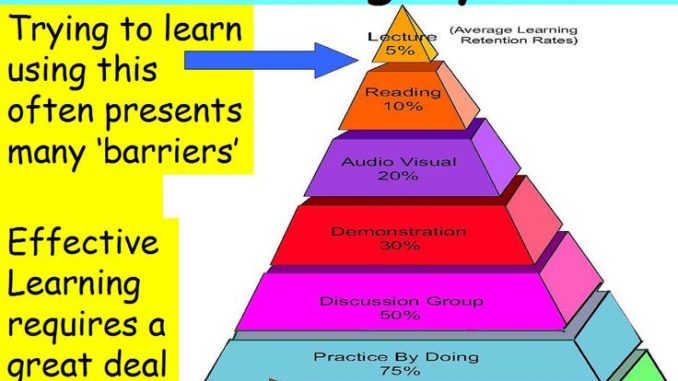

Direct instruction is rather most suited for establishing solid foundations. But there is the danger of too much abstraction. A very guided approach might comfort slow-learners. But maybe there are not really slow learner, just ordinary children who are bored and demotivated. In that case, they might appreciate to have more freedom and more responsibilities. Some students are very happy to engage in classroom discussion. But most of them struggle to get their share of speaking time and some feel very awkward. Lectures are despised nowadays, but people pay a lot of money to listen to a world-class lecturer.

Maybe you are thinking that I’m not going beyond common sense. And it’s true. But. The first thing I’ve learned as a teacher is that nothing is really obvious. “How comes that this kid doesn’t understand my lesson on water, it’s just basic calculation of volume!” But we know that the principle of conservation of matter has to be learned by all the children. Look at Piaget’s experiments. Children don’t understand that the tall glass and the shallow glass can contain the same amount of water before they are sufficiently developed and have done enough manipulations.

The second thing I’ve learned, painfully, is that common sense disappears easily in social interactions. As soon as you have to comply with social norms, or obey political orders, you’ll lose your common sense. It doesn’t matter if you are living in the West or in Asia, if you live under a specific regime or another. You’ll have to align yourself with the norm, at the expense of the truth.

Why are we stuck with low-resolution thinking?

It is important to consider the factors that drive us to low-resolution thinking.

Time is the first one. Teacher trainings are short, we must simplify. Oversimplify. It would take hours to explain constructivism properly. But I can summarize it in one meaningless slogan. We should move from a teacher-centered to a student-centered approach. It works well, because it sounds obvious. But it’s a false consensus. Everybody will agree that schools are meant for the good of the students. But once you’ve said that, you’ve said nothing. You can even say that, fundamentally, learning occurs in the mind of the learner when he’s able to relate new information to his previous schemas. That process can only be done by the learner himself. But even that doesn’t provide clear guidelines about how to teach. After all, the process described by Piaget happens whenever people learn, no matter what the teaching strategy is. If you take time to reflect on my lecture, you’ll learn. Even though it is technically teacher-centered. The question is much more complex that the popular slogan.

The second factor that causes low-resolution thinking is the sequence of learning. Student teachers get most of their training before any professional experience. But you need the experience to really understand what the training means. It’s surprisingly enlightening to read pedagogical textbooks after 20 years of teaching practice, because it makes sense. Pedagogical concepts are blurry until you can relate them to real classroom situations. That’s also a constructivist idea.

You might be surprised to hear that competition as my third factor. Teachers are generally public officers. They don’t view themselves as a part of a competition. We usually associate competition with market economy. But in reality, competition is a part of every system. If there is no competition between schools, there is a strong competition inside the school bureaucracy. And it’s a competition in which the winner takes all. There is no fiercest competition than the competition for power in a communist state. You win or you die. This danger is inherent to public school systems. It’s a huge dilemma. We need norms and structures to ensure a fair and equal access to education for all the children. But there must be only one curriculum. If you want to implement your own wonderful pedagogy, you need to destroy your opponents. Fair conversation is replaced by debates. In a fair conversation, there is no winner or loser. We share points of view that all have their legitimacy. And we can work together to find the truth or at least a common ground. We can disagree and still respect each other. In a debate, I must win. And I must humiliate you, no matter what. I don’t have time for reflection. I must hit where it hurts. I must convince the audience as fast as possible. In the political arena, no matter the regime, you need slogans. Again.

Competition is also an issue in research. You want to distinguish yourself by producing surprising results. If you don’t, you are not published, you don’t get budget.

Pedagogy kills common sense too. It’s probably the most terrifying paradox. One of the easiest ways to explain a pedagogical approach is to make comparisons. You’ll compare your method to the traditional one. But there is no such thing as a traditional method. Tradition is nothing more than the incoherent combination of surviving practices. In order to make a point, we rely on caricatures.

Now, what?

What should we do?

In research, we should be careful not to jump to conclusions.

Don’t put too much trust in statistics. Spend time on your narrative. Make sure that the setting you are testing is sufficiently described. Calculating your p-value will not make your paper more reliable if people can interpret your concepts and learning activities as they like.

Be very careful with meta-analysis. It’s like trying to do facial recognition with compressed images.

In teacher training

Be careful when you compare your method with the traditional one to make a point. The traditional method doesn’t exist. Make sure that your methods are always presented as an option, and are not mandatory.

Don’t promote or dismiss a technique. Extend the toolbox of the teachers. If your technique is really better for the objectives of the teacher, he will adopt it without coercion.

To avoid doing it by mistake, prefer very concrete examples, rather than false oppositions when you explain a pedagogical concept.

Base your recommendations on direct observations. Mentors are the most reliable trainers.

In educational policy

Make sure that teachers feel entitled to make practical decisions. Because they have the circumstantial knowledge.

As much as possible, let the lowest possible level in the hierarchy make the decisions.

Empower teachers!

> Everybody will agree that schools are meant for the good of the students.

It may have been the original goal, but it’s probably ‘lost in translation’ once you go through government policy, teachers unions and more intermediate levels of decisions. Which is why it is extremely important to have a free market in education, to encourage the diversity of approaches and find out, thru market mechanisms, what ends up working the best.

> Lectures are despised nowadays, but people pay a lot of money to listen to a world-class lecturer.

From my experience, it’s because 99% of lectures are extremely boring and ineffective at driving any kind of understanding. World-class lecturers are outliers: it’s almost like they are superstars in the music industry, the very few people capable of selling something to dozens of millions of people while most artists struggle to make a living.

Which is why making “lectures” the default mode of transmitting knowledge is a bad idea: most lecturers are below average, which leads to below average outcomes.